[Note: a shorter version of this article appeared in today’s Davis Enterprise. This longer version gives additional details and background for Commissioner Rowe’s votes.]

By Greg Rowe

Introduction

The planning commission’s marathon December 17 meeting concluded with two recommendations to city council for the proposed Village Farms development: certify the project’s Environmental Impact Report (EIR); and approve the project for a Measure D election. It is expected that by January 20, Council will consider those recommendations and decide whether to place the project on the June ballot. (January 20 is the last meeting date when Council can meet the County’s deadline for June ballot measures.) Voter approval would be followed by a general plan amendment, pre-zoning, and annexation of the site from Yolo County.

I voted against certifying the EIR because of what I am convinced are serious procedural irregularities, based on working with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) since 1984. I likewise declined to support the project because I am convinced its location within a flood hazard zone would compromise the safety of Davis residents within Village Farms.

What is Village Farms?

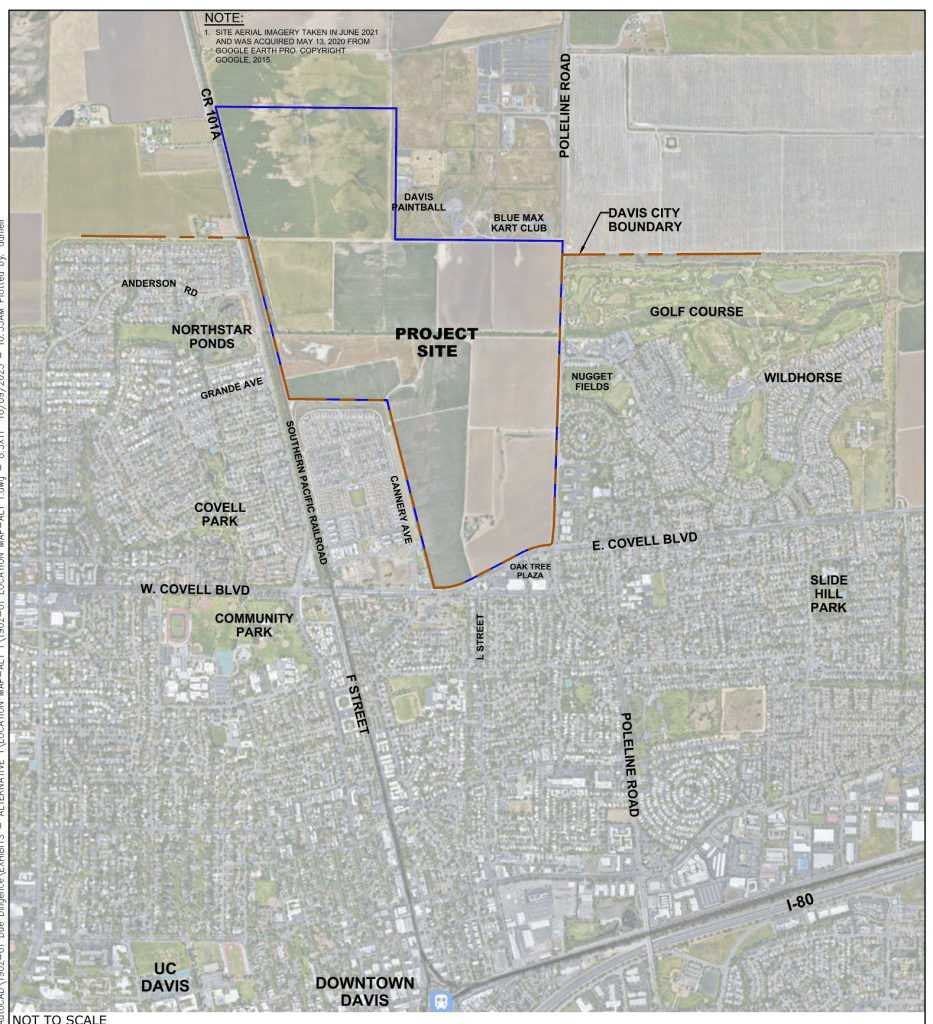

The developer proposes to build 1800 market rate and affordable homes of various types, ranging from apartments to single-family detached homes. There would also be parks, open space, a protected 47-acre wetland habitat, a site for pre-K daycare, and a small land dedication to the City of Davis for public facilities. The property comprises 497 acres situated at the intersection of Pole Line Road and Covell Blvd, extending westward along Covell and north along Pole Line to the Blue Max Kart Club and Davis Paintball.

The proposed project would border The Cannery neighborhood, wrapping around that community on its north side and extending northward along the east side of F Street. A major City of Davis drainage course (“Channel A”) flows west to east through a portion of the Village Farms site. The developer has stated that grading and infrastructure installation would take about two years, and buildout would occur in four phases lasting an additional 15 years. Pursuant to the draft Development Agreement (DA) between the developer and the City, the developer would install grade-separated bicycle and pedestrian crossings of Pole Line Road and F Street.

Climate Change and Floods

The Central Valley has long experienced devastating floods, as described in historian Robert Kelley’s seminal 1998 book, Battling the Inland Sea. The risk of flooding is now much greater because of a warming climate and a higher population that would be exposed to flooding caused by large and intense storms.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) creates flood zone maps for communities throughout the United States, identifying areas of varying flood risk on Flood Insurance Rate Maps. FEMA focuses primarily on identifying areas that have a one-percent annual flood chance, also known as the 100-year floodplain or Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA). High risk flood zones that comprise the SFHA begin with the letter “A”. Such areas have a 26 percent chance of flooding during a typical 30-year mortgage. FEMA flood maps can provide useful information about flood risk, but they do not provide a complete picture, are often outdated, and don’t reflect the impact of increased precipitation induced by a warming climate.

Last September the planning commission received a presentation by the City’s general plan consultant, who identified five climate-related hazard trends that could affect Davis: seismic, wildfire, geologic, severe weather and flooding. The presentation contained an exhibit showing that much of unincorporated Yolo County north and east of Davis is in FEMA Flood Hazard Zone A, including most of the proposed Village Farms property.

The City’s 2020-2040 Climate Action and Adaptation Plan (CAAP) assesses our city’s climate change vulnerability, pointing out that intense rain events and the amount of annual precipitation are expected to increase in the coming years. It concludes by stating “The extent of the 100-year floodplain may increase (and flood depth experienced within it) as climate change causes more intense precipitation events.”

Current Status of Climate Science

The prognoses provided by the CAAP and general plan consultant have a foundation in a scientific model developed by a large, interdisciplinary group of climate scientists at federal and State agencies combined with academic researchers. In 2010 they produced the “ARkStorm Scenario,” which uses sophisticated new modeling techniques to simulate a major west coast winter storm event induced by Atmospheric Rivers (AR). Such a storm, which caused “The Great Flood” of 1861-62 and the large winter storms of 1969, 1986 and 1997, would likely cause massive and devastating flooding in the Sacramento region.

The ARkStorm Scenario report concluded that a prolonged storm similar to what occurred in December 1861 through January 1862 is plausible and perhaps inevitable, and that California flood protection is not designed for an ARkStorm-like event in which 500-year stream flows would be entirely realistic. (The ARkStorm Scenario is on the U.S. Geological Survey website.)

A 2022 journal article co-authored by eminent UCLA climate and weather research scientist Daniel Swain provided the results of updated ARkStorm modeling. The authors noted that the risks associated with infrequent but extreme California floods have been underestimated. They emphasized that “…a growing body of research suggests that climate change is likely increasing the risk of extreme precipitation events along the Pacific Coast, including California, and of subsequent severe flood events.”

Village Farms and Potential Flooding

Predictions of flooding related to a warming climate are highly relevant to the proposed Village Farms project because 306 (61 percent) of the property’s 497 acres are within FEMA Flood Zone A. The developer proposes to address this problem through several actions, which in combination would constitute an untested experiment. First, the top foot of topsoil would be removed from a 107-acre field at the northwest portion of the property. (107 acres equals roughly 81 football fields including end zones.) The topsoil would be set aside for temporary storage.

Then an additional eight to nine feet of soil would be removed from the field, creating a giant pit with its bottom between 9 and 10 feet below grade. The excavated soil, amounting to 1 million cubic yards or more, would be used to elevate the development area above the inundation that would occur during a 200-year flood, the level now required by California law. The developer anticipates this work would reduce the area within FEMA Flood Hazard Zone A to 188 acres, all of which would be in open space or drainage features. (It would take about 100,000 trips by dump trucks with a ten cubic yard capacity to move 1 million cubic yards of soil, although excavators and other heavy equipment are likely to be used for the project.)

The stockpiled topsoil would then be placed at the bottom of the 107-acre depression in the hope that commercial farming could resume within five years. Farm equipment access to the pit would be provided by permanent ramps. The developer wants the 107 acres to receive an “Agricultural” land use designation from the City of Davis, thereby avoiding the cost of a 2:1 mitigation requirement that would entail buying a conservation easement on 214 acres of farm land elsewhere in Yolo County.

The DA includes mechanisms that would be triggered if agriculture is not viable in the depression after five years. Past experience in Davis demonstrates, however, that the City would probably capitulate if the developer were to request a DA amendment based on financial infeasibility or other factors.

The second act of hydrologic engineering would entail rerouting existing drainage channels, installing new drainage infrastructure, and developing an eight-acre detention basin roughly measuring 250 by 1300 feet between the project’s “North Village” and “East Village” neighborhoods. The basin would have an average depth of eight feet, and would temporarily store stormwater until it could drain eastward.

A Better Way Forward

I advocated at the December 17 planning commission hearing for a smaller, compact housing project on the developer’s property outside FEMA Flood Hazard Zone A. What I had in mind was basically a rectangle extending north and slightly west from the intersection of East Covell Boulevard and Pole Line Road. Such an alternative project would be safer and less expensive to build because it would not entail excavating and transporting a massive volume of soil to raise the base level of homes above the floodplain. Building a reduced number of housing units would nonetheless move the City closer to meeting its obligations under the State’s Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA).

Even restricting residential development to the roughly 224 acres south of Channel A would be a far better alternative than the developer’s proposal because it would include far less area within Flood Hazard Zone A. Depending on the density, it might be possible to build 900 – 1000 residential units south of Channel A. This approach was identified as the “Environmentally Superior Alternative” in the EIR for the almost identical Covell Village project proposed at the same site in 2005, which was defeated in a Measure J election by a large margin.

Urban development can’t be completely shielded from stormwater and flood risks, but it would be unwise to build 1800 homes in the potential path of floodwaters based on the assumption that a novel and untested stormwater mechanism will keep residents safe. More housing is indeed urgently needed to ease the affordability crunch and to meet our city’s RHNA obligations, but we should not let engineering hubris and the quest for more housing imperil the lives of those who would live at Village Farms. An old adage says “Mother Nature Always Bats Last,” which could be the case for Village Farms if the project were to proceed in its current format.

______________

Greg Rowe has been a Davis planning commissioner since January 2018. Before retiring he was Senior Environmental Analyst 13 years for the Sacramento County Department of Airports. In that role he represented Sacramento County in a collaborative effort with the Sacramento Area Flood Control Agency that completed the Natomas Levee Improvement Program on County land at Sacramento International Airport.

Leave a comment